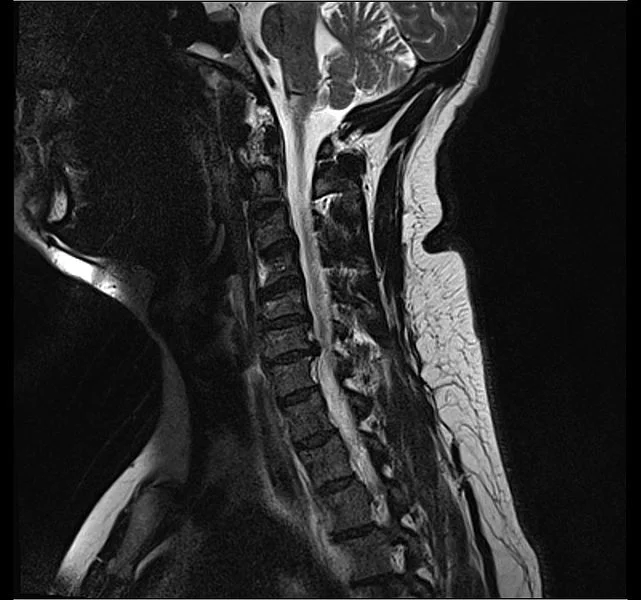

Last week I had my first MRI. I’ve been having back and neck pain since December and had tried a number of treatments to no significant avail, so this was the next course of action in finding out the cause.

Leading up to the MRI, I wasn’t thinking about it very much. People had been telling me about their experiences--MRIs are stressful, loud, you can’t move. (Though I have heard that some people find MRIs relaxing and can fall asleep--if this describes you please email me and tell me how.) I shrugged it off. Whatever, I thought. I’m a meditator. I know how to stay still for 20 minutes, I know how to be with unwanted sounds, I know how to deal with anxiety. No problem.

As soon as I walked in that room and actually saw the MRI machine, it hit me. This is more intense than I expected. I felt my anxiety spike. I felt vulnerable in the beige hospital gown, my glasses removed, lying down with my head locked in a plastic cage. I was told not to cough or swallow because it could mess up the image. I never realized how much I do those things until someone told me not to. I also never realized how much I move, even just micromovements--I probably move in meditation more than I’m even aware of.

But the thing that helped me get through the MRI was not an ability to stay completely still, or to stay completely calm, or to do nothing, or to feel nothing. It was the ability to be with my experience and know what was happening, so I could respond with awareness, so I could know what to do. So I could, from moment to moment, place my attention where it would benefit me, where it would bring me the most ease.

Last week I heard a talk by Sylvia Boorstein, and she defined mindfulness as “the cultivated ability to know what is happening, to hold what is happening in a nonreactive way, in order to have clear comprehension of purpose, of what to do.”

You might not think there’s not much to do if you’re lying in an MRI machine, but there’s TONS to do:

Pay attention to the sounds, or not pay attention to the sounds.

Pay attention to the table vibrating, or not pay attention to the table vibrating.

Open eyes, or close eyes.

Pay attention to sensations of anxiety in the body, or not pay attention to sensations of anxiety in the body.

Widen the attention to notice the whole body. Place attention with breath. With the feet. With the legs.

Be with the specific thoughts arising, or not. Be in conversation with them, or not.

Offer lovingkindess to myself, or not.

From one moment to the next, in order to work with the situation and make it through that experience without being consumed by anxiety, I had to be aware of what was happening in my mind and body, and what would help me find some amount of ease in a divinely uneasy situation.

So I noticed what was happening, and responded from there. What was happening changed, and so what was needed changed.

In one moment, pushing away the sound was too much effort, so I opened to it. In another moment, the sound became too distressing, so I shifted to the feeling of distress and sending myself lovingkindess. The vibration of the table became prominent, so I let that be the focus. The breath, then sound. Anxiety causing thoughts to spiral--zooming in on the specific thoughts themselves and talking to them:

“I’m in danger.”

--No, sweetheart you’re not, this is totally safe, it’s just unpleasant.

“If I move they’ll have to do it all over again.”

--So they’ll have to do it all over again, it’s okay, no big deal. It will just take a little longer.

It was kind of amazing, and probably the most mindful I had ever been in a 25-minute period of time. And that was what allowed me to get through it, and to even walk out of there feeling amazed and grateful for this technology. (And I now have a diagnosis for the cause of the back pain and the beginning of an appropriate treatment plan, which is another kind of relief.)

The experience made me think about how, in practice, the usual instruction is to stay with one anchor--breath, body, sound--and come back to that anchor whenever we drift. And in our formal practice, this is generally helpful, and allows us to have a more conscious shifting of attention when needed. But in our daily life, and sometimes in our formal practice, the most skillful thing is not to stay with one thing, but to make a conscious choice to shift.

Meditation teacher and Rabbi Jeff Roth writes,

“I learned a teaching phrase from Sylvia Boorstein that summarizes the practice of being in the present moment: ‘Whatever arises, don’t duck.’ When you practice you might remember this phrase. But I mention this here to make a counterpoint: sometimes the wisest thing to do is to temporarily ‘duck.’ Sometimes, being with unpleasant states is counterproductive. When the mind is tired out or when the energy is strong and challenging, keeping your attention directly on the challenging energy can cause your mind to wilt or further contract. In this state it becomes more difficult to see clearly, and expending further effort just makes things worse. At such times it can be more helpful to change practices....

“The intention behind our movement away from difficult experiences is of great importance. If we move away in the spirit of aversion, our mind may cultivate the aversive response. If we temporarily leave the difficult mind states for uplifting practices, we need to be honest and aware that we are making this choice. Stating the following intention to ourselves can be extremely helpful and self-accepting: ‘I am switching my practice right now in the service of being better able to deal with this difficult mind state. When I am ready, I will return to it.’” (Jewish Meditation Practices for Everyday Life, page 92.)

Whether it’s an overwhelming emotion, a strong unpleasant physical sensation, an interaction with another person, or whatever, it has been helpful for me to learn to notice the difference between “I don’t like this and would rather this moment be different” and “This is exceeding my resources at this moment, and it would be wiser to take a break or a step back so that I can be better able to deal with this.”

We can check this out when it arises in meditation. Just yesterday during a meditation session, I noticed this arise. I had chosen my whole body as my anchor. At some point I noticed the sound of birds chirping. That’s so nice, I thought, as I noticed my attention start to shift to the sound of the birds. Here I paused: do I need to make this shift, or do I just want to? Is there something overwhelming or unsafe about being with my body right now? If yes, I should shift to the sound. If not, the kind thing is to stay with my body. So I let go of the pleasant sound, and returned my attention to my body. I watched a little wave of disappointment arise and pass.

In the MRI, it wouldn’t have been skillful to white-knuckle it through paying attention to the sound when it became distressing. A high level of distress would not help me get through that time. One could say I ducked from the distress, but it be more accurate to say what I didn’t duck from was the insight that in that moment I needed to duck.

If we can infuse our meditation practice with a prevailing sense of love and kindness, with an intention to care about our suffering, I think the wisdom to know when to duck and when to stay becomes more readily available. It takes practice and feeling our way into it, and probably several instances of staying when it might have been more skillful to have ducked, and ducking when it might have been more skillful to stay. But that’s practice. That’s how we learn to love ourselves, even inside the clanging spaceship of an MRI.

(Image source Wikimedia commons.)

Join Emily this summer for the 8-week Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction course.