Shanah tovah, dear ones. If you’d like to read my sermon from this Yom Kippur with larger font, you can go to the link:

Yom Kippur Morning Sermon, 5785

Mending the Tent with the Thread of Our Grief

With gratitude to the incredible people who offered editing and support in the writing of this sermon: Kate Herzlin, Rabbi Rachel Goldenberg, Kris Wettstein, and Emma Fischer. Tremendous gratitude to the research, writing, and translation work of Annabel Cohen in bringing the practice of Feldmestn back to us.

May there be peace.

-Emily

Mending the Tent with the Thread of Our Grief

Yom Kippur Morning Sermon, 5785

Emily Herzlin

On the morning of my mother’s unveiling, it rained. It wasn’t a torrential rain, but enough that her memorial stone on the ground had become muddy, so muddy that we couldn’t read the inscription with her name on it. Upon seeing this, my heart sank. But my family quickly sprang into action, trying different things to clear the mud: pouring water from a water bottle on it (which made it worse), wiping first with tissues, then with the gauze veil itself (which really didn’t do much). Finally someone suggested using a dry diaper, which we had plenty of because our toddler was there with us. The absorbent diaper wiped up all the mud and extra water, revealing the inscription on the stone. And so, if you are ever in this situation, I highly recommend using a diaper. End of sermon.

But in all seriousness—I felt that my mom, who adored her grandson and was always a fan of dark humor, would have very much approved of all of this, and part of me likes to think that this diaper idea came from her somehow, that she was intervening on our, and her own behalf. After all, theatre diva that she was, she would never have stood for her name not being seen.

After the ceremony, when folks began to disperse, I lingered behind with Rabbi G, who had led the ceremony. She handed me a ball of waxed thread, and held an umbrella over me, walking along behind me, as I placed the thread on the ground, unspooling it, tracing around the circumference of the grave, creating a circle of thread around the perimeter. When the two ends met, I crouched down on the ground, and held the ends together, and prayed. I prayed for my mother’s strength and protection to be with me and with my family this year, for her strength to help bring peace to the world, for a ceasefire, for healing, to make it a good year. I could have kept going, but I was sopping wet despite the umbrella, so I cut the now damp thread, rolled it into a spool, and put it in my pocket to later make a candle with, which I burned here last night at Kol Nidre.

I had learned about this ritual a few years ago through Malkhut and the Shamir collective. The practice, keyvermestn, or feldmestn, means grave or cemetery measuring, and was practiced in the 1800s in Eastern Europe. These rituals were often done in cases of illness or difficult childbirth, and in cases of plague or if a child was severely ill. Threads or candlewicks were drawn or measured around the perimeter of a cemetery (feldmestn) or a specific grave (keyvermestn), and the wicks were then used to create special candles called neshome likht, soul candles. Professionals (usually women) were hired to do the cemetery measuring, and in the week leading up to Rosh Hashanah, the feldmesterins would even wait outside the gates of the cemetery to be called upon to perform the ritual. The candles might then be donated to the Beit Midrash, the house of study, and used to light the study of Torah, or be lit in shul on Kol Nidre. The idea was that the circling, and the contact of the wicks with the cemetery earth, created a connection with the ancestors, with the dead, in order to ask them for their help, their intervention, their protection, on behalf of the sick child or the person in childbirth, on behalf of the living who were suffering.

I read of one feldmesterin, named Gitele, from the town of Koriv in the mid 1800s, Poland. The town rabbi wrote about her:

Upon her arrival in Koriv she quickly made a name for herself among all the women as a very important tsadikes – a righteous woman. And she really was a very pious and God-fearing woman… She had a mountain of tkhines (Yiddish prayers) of all kinds, for every possible problem, and knew all of them almost by heart. She also fasted on Mondays and Thursdays for her whole life. She was the only person in Koriv who measured the cemetery.

One time, Gitele’s ritual was almost ruined by a stroke of bad luck. She was measuring the cemetery for a very sick child, and as she was about to tie the two ends of thread and was saying her famous prayer, the thread suddenly snapped in two! It was almost an affirmation that a child would – God forbid – leave this world. But Gitele – a skilled gabete [pious woman] with a sharp mind and an eloquent tongue – quickly thought of something on the spot, varying her prayer without skipping a beat:

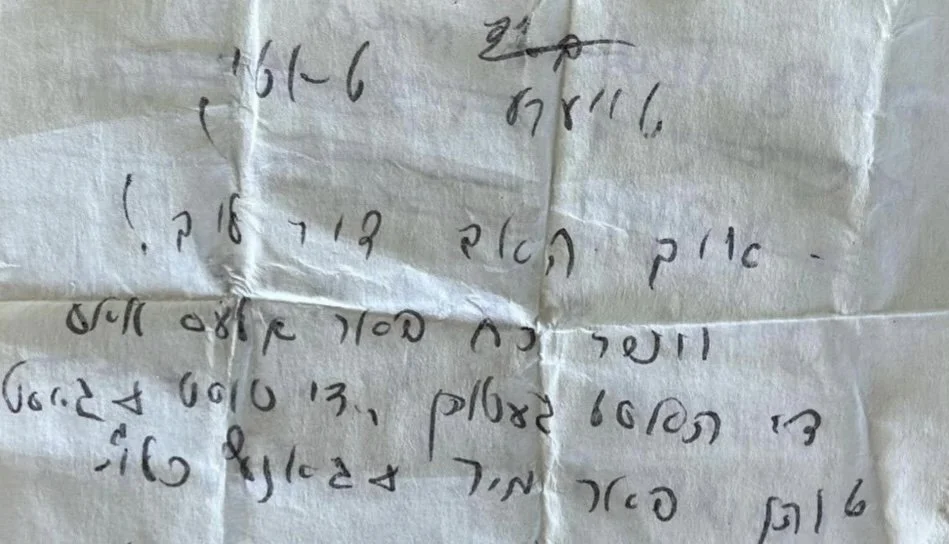

Raboyne shel oylem! Azoy vi der fodem hot zikh ibergerisn, azoy zol ibergerisn vern der beyzer gzardi’n

Master of the universe! Just as the thread was broken, shall the menacing decree of punishment also be broken!

Gitele didn’t pretend the thread didn’t break and move on, she didn’t try to superficially tie it back together, and she also didn’t give into despair at its having broken. She acknowledged it had broken, and turned its brokenness into a prayer for healing.

***

In this year after October 7th, it feels as if many threads have snapped: the thread of the lives of over 40,000 Palestinians, 1200 Israelis, and now over 1400 Lebanese people; the thread of the always-fragile safety of Jews around the world; the thread of the delusion that violent occupation creates safety for anybody; the thread of our taken-for-granted common ground with other Jews. But these threads didn’t just suddenly snap. They had been getting worn down for decades, for over a century, their woven fibers becoming brittle over time as Israeli violence against Palestinians and occupation of the West Bank worsened; as the US quietly continued to arm an increasingly undemocratic Israeli government; as many US Jews, myself included, enjoyed the delusion of not having to think much about Israel and Palestine; as the Israeli government slowly lost its democracy and became more and more fanatical; as Zionists and anti-Zionists issued proverbial herems, excommunications, against one another; until it became too much for the threads, and they snapped.

Before entering rabbinical school, my personal relationship with Israel and Palestine was little more than nonexistent. My family came to the United States before the Holocaust, and no one in my family ever lived in Israel. Despite the efforts of my Hebrew school, I honestly felt no tangible connection to the land. I went on Birthright at the very last possible moment before I aged out. On Shabbat morning during the trip, a rabbi on the kibbutz where we were staying had us stand in the middle of the large room where we had just had our Shabbat service, and asked us yes or no questions. If we answered yes, we went to one side of the room, if we said no, we went to the other side. It was supposedly an icebreaker activity. One of the questions was, “Do you support Israel?” (Mind you this was back in March 2013, a time of no particularly heightened violence, with Americans largely unaware of the continued deterioration of the conditions in the West Bank and Gaza). I watched all my trip mates disperse to one side of the room, you can probably guess which one, while I stayed standing, frozen, in the middle. The rabbi stared at me, raised his eyebrows, as if prompting me to hurry up and pick a side.

Pick a side. I’m still being asked to pick a side, and I’m still standing there, frozen in the middle of the room, unwilling to respond to a question that I think is the wrong question to be asking.

We traditionally read Isaiah for this morning’s haftarah portion. In the text, Isaiah communicates God’s exasperation with the people, who wonder why after they fasted, God didn’t heed their prayers. God responds–is this the fast I desire? People putting on a show of religious performance without doing anything to help those who are dying of hunger and suffering for lack of shelter? Is this really what you think I want?

Pick a side. Do you support Israel? Are you a Zionist? Like God’s exasperation in today’s haftarah portion––is this the fast I desire?–is this really the question God wants us to answer? Perhaps a better question is: is this how we follow Moses’ instructions in this morning’s Torah portion? Is this–the killing of tens of thousands of innocent civilians in the name of our safety—is this how we choose life?

I can’t speak for God, I’m not Isaiah, but to me, here on this earth right now, that is a much more important question to answer.

The Torah, as we know, is full of contradictions. Earlier in Deuteronomy chapter seven, the Israelites are instructed to, basically, enact a genocide on the people who inhabit the land of Canaan, in order to take possession of the land that was promised to them by YHVH. Now, whether or not we believe that the State of Israel has committed genocide against the people of Gaza, we can clearly see what looks like the justification for the violent destruction of an entire people in our holy book. This is painful to acknowledge, and, it is there, and we can understand where it is coming from. (This is going to get a little academic for a bit, so hang in there).

The Israelites who were deported from Judah during the Babylonian exile in about 586 BCE were subjected to overwhelming violence and trauma. The Assyrians threatened them with ethnocide, which historian William Morrow defines as: “the deliberate attempt to destroy the national, ethnic, religious, political, social, or class identity of a group.” The exiled Israelites were suddenly surrounded by a foreign culture, with no boundaries, and no protection for themselves, and were under threat of annihilation. Morrow explains that this led to an increase in aggression towards “a metaphorical entity opposed to faithful Israel.” The violence that the exiles experienced, the same people who would come to author the Book of Deuteronomy, caused them to call for a genocide as a trauma response to the threat of their own ethnocide.”

Morrow also theorizes that the story of the eradication of the Canaanites itself was a necessary step in processing the trauma, as storytelling is a powerful tool in recreating a sense of self after the trauma. He sees Deuteronomy seven as a revenge fantasy similar to those of trauma victims that helps the victim to regain a sense of power and control, as well as to recreate boundaries by “othering” the enemy. In this case, the Canaanites who remained in Jerusalem are seen as the “other,” who are also blamed (especially in Ezekiel, early exile literature) as being responsible for the exile in the first place, due to their sinning against YHVH, as well as their not being of the “in” group. This is part of the genocide justification–to eliminate those who would violate YHVH’s commandments and cause another exile. Morrow explains that “the more a group feels threatened, the more it may dehumanize the enemy-other.”

If this is true, then the Deuteronomy narrative is imbued with a tremendous feeling of threat on the part of the exiled Israelites, which, given the history, is completely understandable. But at what point does a revenge fantasy, bourne out of grief and fear, that we continue to read year after year, shift from being a therapeutic tool to regain a sense of self, to being destructive? As Rabbi G spoke about in her sermon last night, at what point do we need to investigate if those narratives are continuing to serve their purpose, and seek out other possibilities for healing our collective trauma and grief?

***

There is a Jewish custom called kriya, of tearing a garment upon hearing of the death of a loved one. This is a ritual today at Jewish funerals, which I imagine many of you have experienced. These days we often get a black ribbon from the funeral home, so as not to rip our actual clothes, but that was the practice, one is meant to tear their actual clothing in grief. But then what happens with the tear? Do we leave it torn? Do we sew it back together so we can use it again? The Talmud teaches that these tears should never be properly mended. We read in Moed Katan: one may tack them together with loose stitches, and hem them, and gather them, and fix them with imprecise ladder-like stitches. But one may not mend them with precise stitches.

I have to wonder, were the rabbis actually prohibiting this, or was this an observation of how grief works? Once something has been torn, even if we try to mend it, can it ever really be the same as it was before? A year of mourning my own mother tells me, no, it can’t. So instead of trying to cover over the pain, make the cloth look perfect again, what if we were honest about our brokenness?

Even the Mishkan, the portable Tabernacle, was not immune to tearing. The rabbis imagined that through use over time, or from bugs eating the fabric, the tapestries that made up the roof of the Mishkan would rip, and need to be sewn back together. In order to sew the tapestries back together, sometimes that rip would need to be further torn, to create enough space to sew a new seam. (This is actually where the prohibition against ripping or tearing on Shabbat comes from, because it was activity associated with the construction of the Mishkan). So creating a bigger tear from an original tear, was in the service of repairing the container for God’s presence. The tear had to be seen in the first place, and, with an intention to repair it, it had to be ripped more.

This is part of the process of teshuvah. Before we can heal or change our behavior, before we can mend the harm, we have to get a little deeper, we have to allow ourselves to go into the torn place and see what’s there, and perhaps tear it even more, even if it hurts, even if it’s scary, to be able to effectively move forward. And that mending process isn’t about throwing out the old scraps. It’s making something beautiful and hardy from all the old pain.

In my experience of grieving this past year, grieving both my mother and the more global losses, I’ve observed something about how I relate to grief. At times, the pain of my grief, especially when I wasn’t willing to go into the tear, could easily calcify into anger, tightness, a feeling of scarcity and impatience, with myself or with anyone or anything that was in my path. At other times, when I allowed myself to be with the tear, with the pain, my grief was a welcome companion, in that it cracked open my heart in compassion, especially compassion for those who were also grieving, and it sometimes helped to soften some habitual hardness, some grudge, because I knew how it felt to be in pain, and I wanted to lessen the pain for myself and others. How we deal with grief, what it does to us, what we let it do to us, can have great consequences in our lives, our relationships, our communities, our world. Grief can contract our hearts, and often does at first, but, over time, it can widen them.

In our parsha this morning, the Israelites have just wandered in the desert for forty years. The entire generation that was enslaved in Egypt died out. The Israelites had lost faith, and their punishment was that they wouldn’t get to enter the Promised Land. Now this new generation, standing before YHVH, is about to enter into the Covenant, but grief and loss are there, too. Moses says to the Israelites, “I make this covenant not with you alone, but with both “asher yeshno poh imanu…v’et asher aynenu poh imanu omed hayom…” those who stand here with us, and those who do not stand here with us. Traditionally this verse is interpreted to mean the Israelites of that generation, and the future generations. Last year, I drashed that this could mean past generations, too. This year, it’s hitting me differently. Those who stand here with us, and those who do not stand here with us. The ones on the yes side of the room. The ones on the no side of the room. The ones in the middle, the ones in search of a different question. We’ve been doing this for thousands of years–separating ourselves into groups of who stands where, and yet, over and over again, we return to the idea that we need each other. Those who are with us, those who are not with us. We are all going into this covenant together. The question for the Israelites in this moment, the question for us now, is how to move forward in this torn, snapped reality? How to actually mend the tent of the Jewish people, the tent that has been torn by our fear, our hatred, our grief?

We can’t undo the tears in the cloth, we can’t unsnap the thread, we can never be as we were before, and thank God, we are forbidden to try to pretend otherwise. But we can draw new threads around the living, we can circle them around the dead souls and broken delusions, and with those threads we can begin the repair. We tear a little deeper and go into the hurt places–we investigate our inherited trauma; we explore how it is possible to be in a single moment both the oppressed who were liberated from Egypt and the Pharaoh oppressing others; we try to relax our shoulders and exhale Biblical tribalism (want to try it? Go ahead, let’s try it), and breathe in our responsibility for all living beings. We can look at each other’s faces, people we know, people we don’t know, we can envision the faces of people in refugee camps or tents or bomb shelters, and see in each face a human being who wants to be safe, peaceful, healthy, and happy, just like me, just like you.

Then, and only then, can we truly mend the tent, with zig zag stitches and patchwork and honesty and clarity, so that we can see the rips and tears as part of our holy history. So that, every day as we work for peace, we sew with thread made of the sturdy truth of who we are, not of the flimsy delusion of who we thought we were. And when we look up at the tent, we may see it looking scrappy and perhaps not so pretty, but we will be confident that this sacred tent we are creating and recreating together is strong enough and spacious enough to hold us all.

And so now as we move through the graveyard of this past year, taking in all that we have lost, let us place the thread on the ground, unspool it, trace around the circumference, creating a circle of thread around the great perimeter of our grief. When the two ends meet, let us crouch down on the ground, and hold the ends together and pray:

Raboyne shel oylem, just as the thread was broken, shall our inclination to separate and dehumanize one another also be broken. May we see each person in their wholeness, may we see all living beings as one family, and may we call upon the power of our grief to guide us to choose life.