Accessing Our Be’er Tamid–A Limitless Well of Joy

Kol Nidre Sermon 5783

By Emily Herzlin

Sermon given on Kol Nidre at Malkhut services at CUNY Law School, Tuesday Oct 4, 2022

Before I begin I want to give a content warning that for the beginning of this sermon I will be mentioning miscarriage, nothing graphic, but just know there will be some brief mention of it.

As many of you know, I gave birth in March to our sweet baby, Lev. Most of you probably didn’t know this, but last High Holidays, I was up on the bimah helping to lead Malkhut services in the beloved but un-air-conditioned church in Jackson Heights, firmly in the throes of first trimester nausea, sneaking off the bimah to try to covertly eat crackers.

But what even fewer people knew–a week before Rosh Hashanah when we went for my 8-week sonogram, the doctor informed us in the same breath that I had become pregnant with twins, but one of them did not have a heartbeat and likely would not develop one. Kris and I were shocked. The High Holiday theme of “who shall live and who shall die” had become painfully present and literal for us.

We prayed during Rosh Hashanah for that little heartbeat to show up, but when we went in again, a few days before Yom Kippur, the doctor confirmed I had had what is called a “twin demise,” one of the fetuses had miscarried.

I later learned that over a third of twin pregnancies experience a twin demise, usually because of a chromosomal abnormality that makes one of the fetuses incompatible with life. I wish I had known how common this was, and that there was nothing I could have done to prevent it. It wasn’t anybody’s fault. It just, sadly, happens.

At that moment hearing the news, I experienced complex grief. In the Jewish tradition, life begins when the baby takes their first breath, not at conception, a disconnect that has been very clear this year with the overturning of Roe v. Wade. But one of the things I realized I was grieving wasn’t just the loss of this potential life, but the fact that I never got to be excited about it. I felt like I missed out on experiencing extra joy at the possibility of having twins, even though it would have been for just a few weeks, and may have intensified the loss I felt. But still, I was sad I had missed out on it.

Then the doctor panned the sonogram wand over to the fetus that was doing well and ON. THE. MOVE. There it was, I could make out tiny arms and legs, swimming and somersaulting and suddenly I felt a surge of joy like I had never felt before. (Even talking about it now, I feel that surge of joy). But as I lay there, I kept questioning the joy, judging it, feeling guilty about it, getting in my own way of experiencing it. I kept thinking, I should be worried, I should be sad. But the joy was there, and it wanted my attention. It wanted to nourish me. I wouldn’t let it.

A lot of us struggle with joy in general in our lives. Joy. It never felt to me like a particularly Jewish word. Joy to the world, it sounds like Christmas. It sounds off limits. My grandparents loved to quote the Mel Brooks line, “hope for the best, expect the worst.” During my pregnancy I’d reflexively tense up when someone said “congratulations.” Ashkenazi Jews customarily don’t say congratulations or mazal tov before the baby is born, because we don’t want to invite the evil eye. Instead we are apparently supposed to say, “b'sha'ah tova” - “may it come at the appropriate time.” Lot less fun. My family asked about a baby shower. I said, sure, not realizing until someone told me later that it’s an Ashkenazi custom to refrain from a baby shower for the same reason–not to invite something bad to happen. I learned that it is not actually halakha, not Jewish law, but it is a pretty well-worn custom to not have a baby shower. But I just couldn’t fathom both not preparing in ANY way for the arrival of our baby, or denying our very excited families the chance to rejoice in the anticipation of our growing family. And so in an act of anti-Ashkenormativity, Kris and I ended up having not one, but THREE zoom baby showers, because of our large families, and they were wonderful and full of joy.

Throughout my life, I came to believe that joy was scary. If you let yourself get too happy, something bad would happen. I think a lot of us feel that way, so we defensively keep an experience like joy at a distance. We have a general sense that something is pleasant but we don’t fully let go into the joy, we don’t immerse in its depths, we stay up at the surface. I think that people who have experienced persecution or, like many Jews, who carry the intergenerational trauma of persecution in our bodies share this experience to an extent. And while this analysis is helpful in understanding the general hum of anxiety many of us feel on a day-to-day basis, it isn’t enough to heal the anxiety.

In these past several years of the pandemic, I have come to have a newfound respect for joy, and a clearer understanding of why it isn’t just a luxury, but how it is vital and medicinal, and how it’s often necessary to take active steps to cultivate joy rather than wait for it to show up.

Jewish teacher Yael Shy frames the concept of joy, not in the sense of being happy or positive all the time, rather, “Joy as a state of expansive contentment, of deep okay-ness, even when everything is going wrong, and there is so much to do, and the world is burning. Joy as a sustaining and sustainable center within us that can hold all of it. Joy that can be IN life, just as it is, instead of constantly being pushed around by life. Joy that gives us options in how we want to respond and use our time on this earth wisely.”

Our Jewish tradition has a lot to say about joy. Listen to these gorgeous Hebrew words and synonyms for joy: Simcha. Sasson. Alazah. B’dichut. Tzohola. Geela. Oneg. Deetza. Chedva. Masos. Rina. Alizut. At least 6 of these show up in the sheva brachot that we say at weddings. The month (or two) of Adar is considered a time of increasing joy. During the Festival of Sukkot that’s coming up soon, we are commanded: v’samachta b’chagecha. Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg points out that while this is often translated as that we are commanded to be joyful, a more accurate translation is that we are commanded to get together and have a festival. In other words, we aren’t commanded to FEEL joy, rather to create conditions that make joy possible.

Now you might be thinking, hold on, Emily. Look around. We are not at a wedding. It’s not Sukkot. We still have Yom Kippur to get through. Why are you talking about joy right now? In case you haven’t noticed, the work of teshuvah–returning to our places of suffering in order to repent or repair or heal–is hard. It’s not pleasant…to which I say, yes, AND if we are really going to deeply engage in that work, it’s going to take a lot of energy. All the more reason why we need to sustain our energy through the process, not just through the Yamim Noraim, but all throughout the year.

This is where the Buddhists have some wisdom to offer us. In the Buddhist tradition, joy isn’t just a feeling. It’s not something we have or we don’t, it’s something we can cultivate. It is part of a family of 4 intertwined qualities called The Four Immeasurables, meaning they are available without limit. The other qualities are lovingkindness, equanimity and compassion. In the Buddhist tradition, these 4 qualities all support the others–each one cannot exist without the other three. In other words, Joy and Compassion, (simcha and rachamim) are not separate. I’ve thought about this a lot over the years–how compassion–the resonating of our hearts in response to suffering and our efforts to then alleviate that suffering–is not possible if it is not balanced by a healthy dose of joy. This is one of the lessons of the pandemic for me–one of the major sources of sustaining energy for me during this long protracted time of suffering hasn’t been just rest, it’s been joy, however and wherever I can find it. In the darkest days of the pandemic, it was in the buds on the trees, making fresh pasta, the little peppers I grew out back, the Malkhut services on zoom. Like Yael Shy wrote, it wasn’t about feeling happy or positive all the time, but more like drinking deeply from a wellspring of nourishing water, not just when I was dehydrated, but on a regular basis.

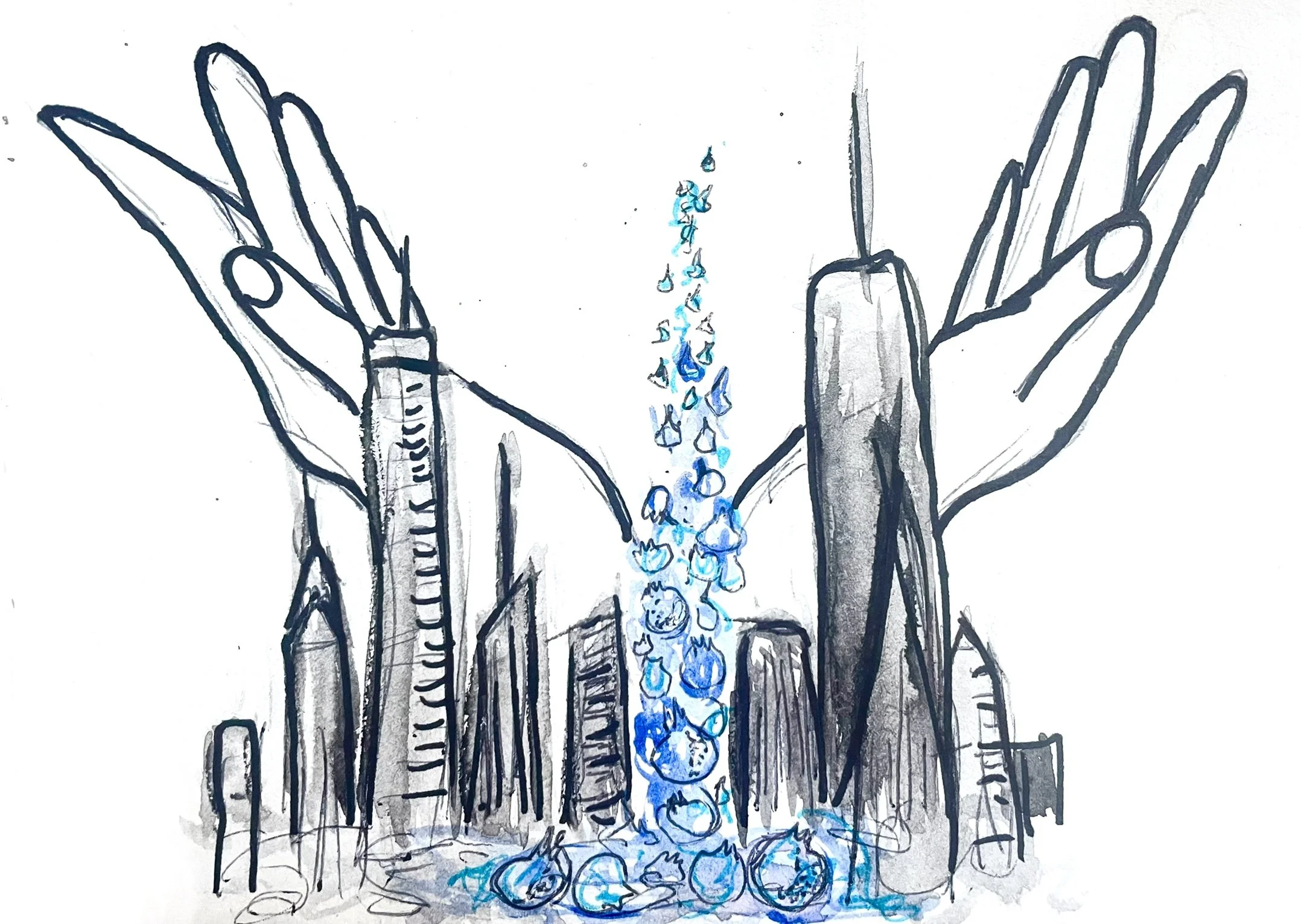

In sanctuaries throughout the world, there is the eternal flame that glows continuously. The ner tamid: tamid–continuous; ner–flame, ner tamid. The Hebrew word for a well of water is be’er. If you’ll permit me a moment of Hebrew nerdery: What if we could learn how to draw up nourishment from our own personal, reliable, immeasurable, be’er tamid, whether externally or in our imaginations?

I’d like to invite you to take a moment, rest or close your eyes. (If any of the guidance I’m about to give isn’t right for you it’s fine to refrain from this practice and just rest for a minute or two). But if you’re able, inviting into your awareness a moment of joy or something that brings you joy. I’d recommend choosing something that’s relatively mundane. Petting your cat. Tasting really good tea. Receiving a compliment. Recreate the moment, the scene, and notice what it feels like your body, notice any subtle or strong sensations of pleasure, ease, gratitude, joy…noticing where you feel these sensations in your body…in your face, in your chest, in your limbs…maybe it’s warm, maybe it’s relaxed, maybe it’s tingly…seeing if you can notice it, and rest with it for a moment, without analyzing it, questioning it, judging it. Immersing in it, letting it bathe your entire body, heart, mind. Drinking it in…. Letting yourself be nourished and renewed by the wholesome pleasure of joy. And if you don’t feel anything, that’s ok, just being open to the possibility of joy is planting a seed that may come to fruition later... Letting your eyes open or raising your gaze when you’re ready.

We need more joy in so many parts of our lives. Activism is one place in particular. Rebecca Solnit, author and activist writes of the climate movement, “Our movement cannot thrive if we’re nothing but a puddle of doubt and denial. Us getting locked into a commitment to doomism may allow us to emotionally self-congratulate ourselves…, but it will burn out movement energy.” To this end, Solnit has recently started an initiative called Not Too Late, which publicizes the GOOD climate news, the victories no matter how small, to bring a more balanced perspective to all of us who feel a sense of hopelessness at the enormity of the task before us.

A lot of social justice work is, understandably, powered by guilt and fear. But it’s worth entertaining the possibility that guilt and fear are not the most sustainable fuel sources. In her research, economist Trisha Shrum found that helping the environment gives people a “warm glow”--which is apparently an adorable economics term, but is also a way of describing the physical feeling of joy in the body. Maybe you felt that warm glow during our guided practice a few moments ago.

Shrum says, “we’re starting to see that not only do people feel good about themselves when they do something good for the environment, but this anticipation of that warm glow…is one of the strongest drivers of pro-environmental behavior.” In other words, says Shrum, the warm glow from environmental action leads people into a “virtuous cycle,” where the good feelings are sustaining and nourishing to the person and help them want to continue. “How cool would it be,” Shrum asks, “if we figure out the best way to save the planet is to have more joy and have more fun? That’s the best ending. Like if I could write the book of How I Saved the Planet: We Had a Big Party, It Was So Fun.”

While I don’t plan to turn Yom Kippur into a big party necessarily, on this Kol Nidre night I want to make a case that God actually wants us to experience joy.

We read in tomorrow’s Haftarah portion in Isaiah:

“Why, when we fasted, did You not see?

When we starved our bodies, did You pay no heed?”

…Because you fast in strife and contention,

And you strike with a wicked fist!

Your fasting today is not such

As to make your voice heard on high.

Is such the fast I desire,

A day for men to starve their bodies?

Is it bowing the head like a bulrush

And lying in sackcloth and ashes?

Do you call that a fast,

A day when YHVH is favorable?

I want to pause for a moment to notice that phrase: ”a day when YHVH is favorable,” “ yom ratzon YHVH.” Ratzon we generally translate as acceptable, willing, favorable, but it comes from the same root as רצה Ratzah, which can also mean…pleasure! To be pleased. Do you call that a fast, a day YHVH is pleased? In other words, God is not pleased if our repentance is fueled by harshness and self-hatred. God won’t actually accept our repentance if it comes from such a source.

So, what are we doing here, and to what end? The text continues:

No, this is the fast I desire:

To unlock fetters of wickedness,

And untie the cords of the yoke

To let the oppressed go free;

To break off every yoke.

It is to share your bread with the hungry,

And to take the wretched poor into your home;

When you see the naked, to clothe him,

And not to ignore your own kin…

Then shall your light burst through like the dawn

And your healing spring up quickly;..

He will slake your thirst in parched places

And give strength to your bones…

You shall be like a watered garden,

Like a spring whose waters do not fail.

That spring that flows continuously, that’s that warm glow of living in alignment with our values. Righteous action feeds joy, joy feeds our righteous action in the world. Virtuous cycle. The process of teshuvah is unpleasant, but think for a moment of a time when you changed a destructive habit, made a different choice towards healing and even better, realized you made a different choice. That moment of healing, of positive change, brings us a feeling of ease, peace, contentment, freedom, joy.

Yom Kippur has the potential to be the MOST joyful of the Jewish holidays. If every person in every congregation all over the world were to actually follow through on our prayers, the world could be completely changed. Take a moment to envision a world where all the people in this room, and in similar rooms, and sanctuaries and living rooms, transformed our places of stuckness and experienced healing in our selves, communities, systems, and world. How much joy would come from that. Take a moment to feel that. Noticing, perhaps, a felt sense in your body right now, of olam haba, the world to come.

I want to close with a prayer that each of us on our own and collective paths of teshuvah, may always have access to our be’er tamid, our inner well of joy, whose waters never fail.

As we sing together a song by Sarina Partridge, I invite you to imagine drawing up from the waters of your be’er tamid whatever it is you need at this moment.

(Image by Lisa Huberman)