Under the Mountain, Choosing Life

Yom Kippur Sermon 5784

Emily Herzlin

Red Point Fault Line, Grand Manan, NB

In early July, my son Lev, and my spouse Kris and I took a trip to Grand Manan, an island off the coast of New Brunswick. It’s a geologist’s dream, rocks and formations from different eras all converging on this one island. On one beach in particular there is a trail you can follow and if you look closely, you can spot a diagonal line in the cliff face–a fault line. On one side of the fault are rocks from 539 million years ago; on the other, rocks from just 201 million years ago, and here, where the cliffside meets the beach, the fault line is exposed and you can see the eras converge.

Kris and I had visited this island a few times before but we never found the fault line. This time, on our walk along the beach on a particularly foggy morning, Kris saw it. Perhaps the dense fog, obscuring our view of the beach and the ocean, had served to focus our attention on just what we could see in front of us. There it was–the long diagonal line slicing through the cliff face. On one side the rocks were reddish and crumbly, the other gray and chunky. The line between them was white, calcified stones. A tiny stream flowed from the top of the cliffs, eroding some of the red rocks down the sand of the beach in a pink-ish trickle towards the Atlantic ocean. We walked over and stood directly in front of the line in the cliffs, this clear visual representation of time, of history, of different moments in the past, slashed plainly in two. And now my baby’s tiny hand, in the year 2023 or 5783, touched the rocks, touched the beyond-ancient past, as the waves of the Atlantic rolled in and out behind us.

***

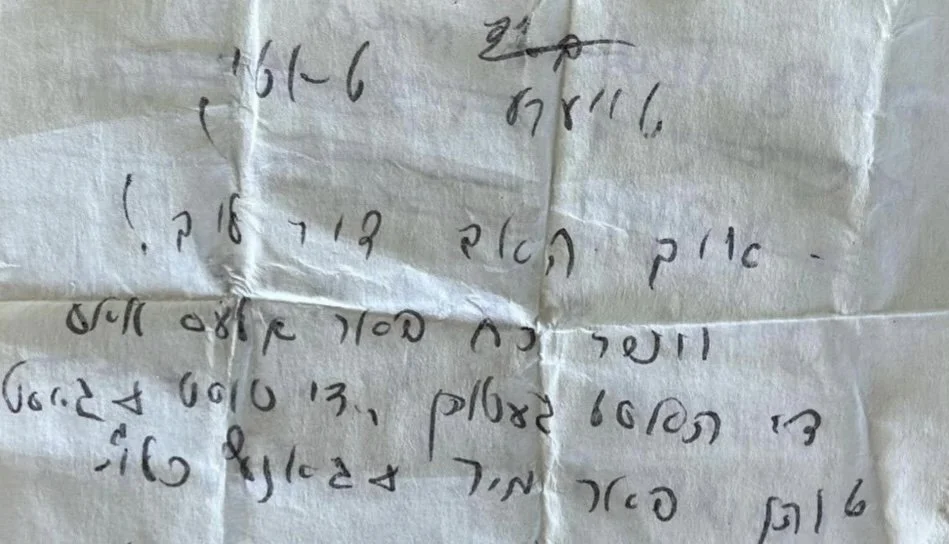

A few days later, those waves washed up a mystery, or maybe it was a miracle. A resident posted the following to a local island facebook group:

“Found this note in a balloon on Cheney Island, can anyone decipher it.” (Cheney Island is a small uninhabited island that is part of Grand Manan). The photo attached was of an unfolded piece of paper, slightly ripped, with non-English lettering. In the comments, folks hypothesized it could be Portuguese, Inuktitut, but no one could figure it out. I could tell it was, improbably, Hebrew cursive. (Mind you this is not a very Jewish part of the world. I believe that while my interfaith family was visiting the island, the Jewish population there was probably a total of 2, me and Lev, and zero when we left, so this was a big mystery, where did this come from?) I posted the photo to my rabbinical school slack channel for help translating and also shared it with Rabbi G. Several people worked on deciphering the scraggly, smudgy text alternating between Yiddish and Hebrew text. Here’s what we came up with:

“Dearest,

Oh how I love you.

Thank you for everything

That you have done, the lazy and the spirited

Do it for me and everything.

Please send healing

Salvation and sustenance, planting seed.

Joy life grace

Spread out from the four corners of all the earth.”

At the bottom of the letter, crossed out, there is a prayer for the ascendance of the spirit of a deceased woman named Rivka, daughter of Simcha. The note is dated from the year 1961. (We think–this part was hard to decipher, it either looks like the date 6-61, or the word Tati, a Yiddish term of endearment for father, which could be someone’s actual father, or a reference to God. So anyone fluent in Yiddish who wants to help settle a debate, get in touch with me).

To me this reads like a prayer to God–a prayer of thanks, request, and praise. The author sent it off across the sea, trusting that somehow, it would reach its destination.

In this morning’s Torah portion, the Israelites are on the verge of entering the Promised Land. In some of Moses’ last words to them before they cross over and he dies, he says:

Surely, this Instruction which I enjoin upon you this day is not too baffling for you, nor is it beyond reach. It is not in the heavens, that you should say, “Who among us can go up to the heavens and get it for us and impart it to us, that we may observe it?” Neither is it beyond the sea, that you should say, “Who among us can cross to the other side of the sea and get it for us and impart it to us, that we may observe it?”

As Moses sends the people off into the unknown, he reassures them they will know how to fulfill the covenant even after Moses is gone. In turn, the people can trust that the Divine Presence will be close and accessible to them even though God will no longer be visible to them as God was in the desert, as a pillar of cloud or fire.

This time, with the help of a beachcomber, and a couple of 21st century rabbis and rabbinical students, someone’s prayer that was set off to sea, entrusted to the wisdom of the waves, was received and read and known.

Still I wonder if the author ever felt like their prayer had been answered, or if they got what they needed just from letting their prayer go.

***

The Torah portion continues:

I make this covenant not with you alone, Moses addresses the people of Israel.

But both with those who are standing here with us this day before our God יהוה and with those who are not with us here this day.

Meaning those who are here, and those who are not here, are all entered into the covenant.

How do you make an agreement with people who aren’t here? Seems like bad HR protocol. And who isn’t there anyway? We are told that all of the people of Israel are there: Every householder, official, child, wife, stranger, woodchopper, water drawer, every person. So who is not there?

When I first read the parsha, I thought “those who are not here” meant the ancestors, the dead, those who had come before us. Then I remembered that Jews are a little uncomfortable when it comes to being in relationship with the dead, it was all too pagan-y feeling for the scribes of the Torah. But at weddings, at simchas, we pause to remember and invite into our minds and hearts those who have died. There was even a practice in some communities in Europe of going to the cemetery to invite a bride-to-be’s deceased family members to attend the upcoming wedding. So wouldn’t we invite the ancestors to witness our commitment ceremony to the covenant?

But I dug a little deeper, and learned that according to Rashi, “those who are not with us here this day” doesn’t mean those who were, it means those who will be. The generations to come. Us. Whether we wanted it or not, whether we feel prepared for it or not, this covenant is ours.

There is a midrash that, earlier in the Torah, when YHVH originally charged the people with the covenant, he lifted up Mount Sinai over the heads of the Israelites, upside down, and said, “If you accept the Torah all will be well, and if you do not, this will be your burial place.” In the midrash, YHVH is threatening to crush the people with a mountain if they don’t agree to the covenant. If it sounds coercive, that’s because it is. Commentators explain that if chosen totally voluntarily, a person might later go back on their agreement. But if there was some element of being forced to accept it, they won’t be able to turn it down.

While I needless to say have issues with this tactic, it’s not entirely inaccurate to my lived experience. There are so many things in life that we don’t get to voluntarily choose, that we then have to choose to find a way to be with.

Thirty days after we buried our mother, after she died suddenly and unexpectedly of a stroke, my sister and I sat on my couch, an upside down mountain hovering over us, and my sister said to me,

We can’t control that we are now the next generation.

We didn’t get to choose that this is our time.

But now we get to choose what we do.

We are responsible for what happens next.

We all need to find our way forward, into the Land-of-What-Comes-Next, to follow the parsha’s instruction, Uvacharta bachayyim, to choose life. Anyone who has experienced grief, depression, fear, stress, can recognize those heavy, stuck moments, standing underneath an upside down mountain. And every time we make the choice to write a shopping list, to sing a song, to cook pasta, to be kind to the customer service rep on the phone, to get on the bus, to get the bloodwork done, to do the crusty dishes, to give ourselves the rest we need, to breathe in and out, we choose life.

The upside down mountain is not so much a threat, as it is a depiction of what it is like to be human and to have to make choices without knowing if they are the right ones–if the mountain will fall, or stay aloft, if our choices will cause suffering, or liberation from suffering, or both. Sometimes it’s clear, but a lot of the time, at the moment of decision, we don’t know. Sometimes we don’t ever find out. Under such unsatisfying conditions, how do we access the chizuk–the strength–to choose, to act, to move?

***

Our tradition is uncanny when it comes to time. There’s a thin veil between the past, present and future, with holes like cheesecloth where every now and then you can touch fingertips with someone from another time. On Passover we see ourselves as having left Egypt; on Shavuot we see ourselves as having received revelation at Sinai; on Sukkot we invite the ushpizin, the ancestors, into our sukkah to rejoice with us; on Yom Kippur we imagine we are preparing for our death, for a world without us, much like how the Israelites in our Torah portion who are waiting to enter the Promised Land imagine themselves making a pact with those who they do not yet know, will never know, who will be here long after they are gone. Charging us with a most precious and beautiful task–to make a blessing of their memories. To carry on their Torah.

Can you imagine the level of trust necessary to feel that, when you are gone, the world will be okay? To trust that the work we did while we were alive created causes and conditions for goodness and love and healing to continue to unfold? I aspire to that level of trust. I aspire to the level of trust of a person who puts a prayer in a balloon and releases it and trusts that it will get where it needs to go.

Our doubt in our ability to adequately show up for this task has been anticipated by our ancestors (probably because they felt it too). It’s in the verses we heard earlier when Moses tries to reassure the people as he charges them with the covenant: it isn’t out of your reach, up in the heavens or beyond the sea. “No, the thing is very close to you, in your mouth and in your heart, to observe it.”

As this Yom Kippur day atones for us and sets us up for another year of being perfectly imperfect, the upside down mountain resumes its spot hovering over all the people of Israel, over all of us. Look up. Can you see it? Suspended in the air, reminding us it’s time to renew a commitment we didn’t choose to make in the first place.

To once again quote my wise sister:

We can’t control that we are now the next generation.

We didn’t get to choose that this is our time.

But now we get to choose what we do.

We are responsible for what happens next.

This is the choice we get to make on Yom Kippur. Not to be coerced into something vague and threatening, not to feel guilted into going to shul, but to decide for another year that we want to be awake and present and act with wisdom and kindness and justice. To decide that we want to live our Jewish values in our daily lives because it’s who we are, and living who we are is good. It’s good for the world, it’s good for the generation who will one day be without us, and it’s good for the generations who came before. Because living who we are is how we prove ourselves worthy of our ancestors’ trust, how we show they were right to believe in us, and how we model for future generations how to show up for our memories one day.

Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh z”l wrote after the death of his mother: Walking slowly in the moonlight through the rows of tea plants…Each time my feet touched the earth I knew my mother was there with me. I knew this body was not mine but a living continuation of my mother and my father and my grandparents and great-grandparents. Of all my ancestors. Those feet that I saw as "my" feet were actually "our" feet. Together my mother and I were leaving footprints in the damp soil.

When we knock on our hearts with our fists, when the sounds of the shofar enter our ears, when we feel our breath between the words of the Shema, when we feel our lips touching a dear one’s forehead–those who are not here, our ancestors who entered us into the covenant, are here with us in our going forward into the Land of What-Comes-Next. Maybe when we feel like we don't have enough chizuk to choose life and lift ourselves up and move, it is our ancestors who give us that strength, that push. They reach through the cheesecloth or across the faultline of time and space and move us, whisper to us, "Keep going, you've got this. Do it for me, and for everything." They journey with us, as we will journey with those who are yet to be, who will inherit the world that we are cocreating now. Another layer of rock, upon layer, upon layer, upon layer.

So, maybe we can let go of needing to have all the answers taught to us by our elders before they are gone. Because our bones, our eyes, our ears, our tongues, our feet, our bellies, already know the Instructions for how to live, even if our minds haven’t caught up yet.

To those who came before us: we offer you our gratitude, we look to you in awe, we forgive your shortcomings, and we will strive to continue to make of your memories a blessing and carry on your Torah, in our mouths and in our hearts;

May those who are not yet here graciously accept this world that we who are here today are doing our best to leave in better condition than we found it, may you understand our struggles, and forgive us, for all that we were not able to do for your sake, and may you recommit to and build upon our work in your own unique and important ways;

And for all of us assembled today, as we touch the fault line between the year that has passed and the year that is beginning, may we make the choice to accept upon ourselves the covenant that we’ve already been entered into, may we show up to our lives as fully as possible, offering the life-giving actions that are ours to offer. And let us turn towards the waves and send our prayers off into the ocean, with our perfectly imperfect faith that they will land somewhere and be heard.